Early last month, we outlined how automobile sales deteriorated in late summer and prophesized carmakers

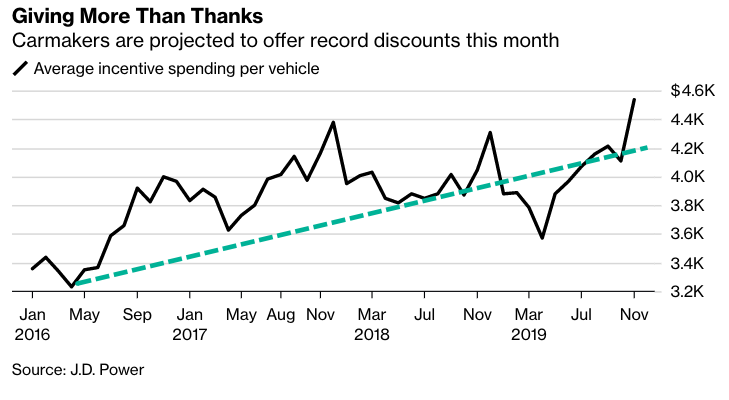

It seems that we were right. Automakers are now offering the most discounts on record to entice deadbeat consumers in November, according to a new report from JD Power.

The average incentive spending per vehicle is $4,538, an increase of 12% YoY. The previous high for the industry was $4,378 in 4Q17.

Inventories for

With the average APR to finance a vehicle around 5.3% for the month, the average transaction price remained above $34,000, down from $179 from last month but up $622 over the year.

As a result of low rates and record-high incentives, consumers spent $40.3 billion on new vehicles in November. This figure is up $2.7 billion from 2018.

Thomas King, Senior Vice President of the Data and Analytics Division at JD Power, said, manufacturers will offer even greater incentives through December, and the trend could continue into early 2020.

"Incentive spending typically rises by 3-4% in December, which would continue to drive overall spending to unprecedented territory," King said.

King warned: "This [incentive trend] is concerning

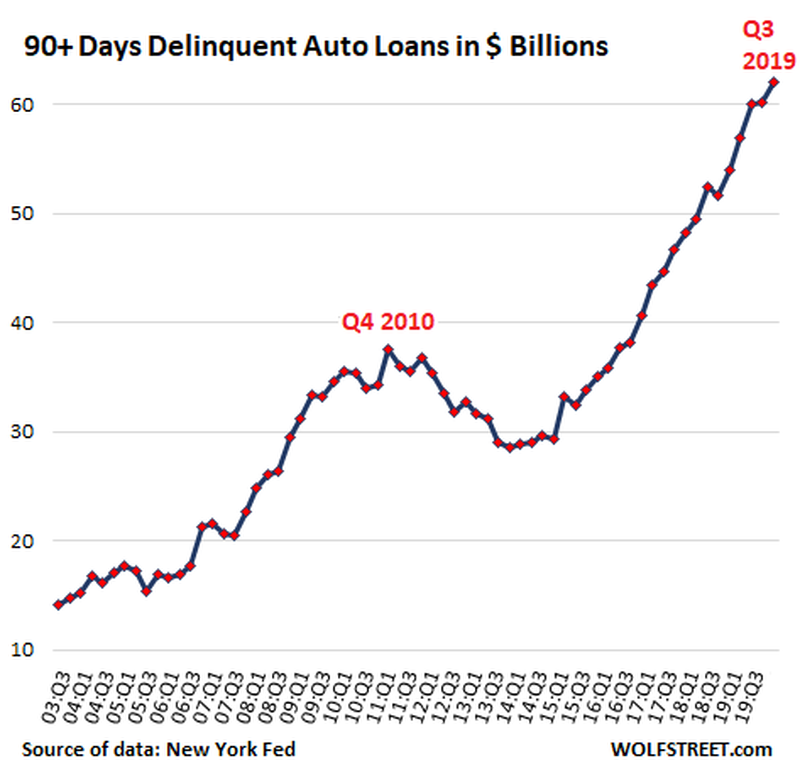

We recently noted serious auto-loan delinquencies (more than 90 days past due) in Q3 hit a historic high of $62 billion.

"This $62 billion of seriously delinquent loan balances are what auto lenders, particularly those that specialize in subprime auto loans, such as Santander Consumer USA, Credit Acceptance Corporation, and many smaller specialized lenders are now trying to deal with. If they cannot cure the delinquency, they're hiring specialized companies that repossess the vehicles to be sold at auction. The difference between the loan balance and the proceeds from the auction, plus the costs involved, are what a lender loses on the deal," wrote Wolf Richter via WolfStreet.com.

Automakers are recklessly blowing up a $1.32 trillion bubble, by ramping up subprime loans to deadbeat consumers. Recent incentive increases have taken the bubble blowing to an entirely new level that is not sustainable.

Germany's Car Jobs Boom Comes to a Screeching Halt

Unlike its Detroit rivals, the German auto industry didn’t have to slash its workforce in the last recession. How times are changing.

After a week in which Daimler AG and Volkswagen AG’s Audi announced thousands of job cuts, it’s easy to forget that the German car industry once seemed unassailable.

The 2009 recession forced a massive downsizing of America’s auto giants. General Motors Co. and Chrysler filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection; Ford Motor Co. escaped a similar fate only by cutting its workforce to the bone. By contrast, Volkswagen, BMW AG and Daimler’s Mercedes-Benz overcame the crisis with barely a scratch. Afterwards they took full advantage as wealthy Chinese splurged on luxury German vehicles. Germany’s carmakers and their suppliers went on a hiring spree at home and abroad.

Jobs Boom

Germany's biggest automotive groups just kept on hiring

Source: Company reports

These jobs aren't all car-related: eg Daimler and VW make trucks while Bosch and Conti have industrial activities. VW Group includes Audi. The data are not adjusted for acquisitions: eg at Continental in 2008 and Bosch in 2015. 2019 refers to the most recent available data.

There were early signs of hubris: Volkswagen paid its chief executive officer 17.5 million euros ($19.3 million) in 2011. But Germany’s powerful trade unions made sure workers benefited too. In recent years production line staff at BMW and VW’s Porsche subsidiary took home almost 10,000 euros as an annual bonus. BMW spends an average of more than 100,000 euros per employee on salary, pension and social security costs, according to its annual report.

Now that jobs boom has come to a screeching halt, and not before time. An industry facing unprecedented upheaval can’t afford such largess.

German Inefficiency

U.S. carmakers achieve more with less (though BMW is quite productive)

Source: Bloomberg

The chief reason for the belt-tightening is, of course, the vast cost of moving beyond combustion engines. Volkswagen expects to spend an astonishing 60 billion euros on hybrid, electric and digital technology in the next five years. Doing this requires the hiring of even more people, but the products they’re developing aren’t always big money spinners yet.

For a time, the industry will have to provide a full range of propulsion options. For their factories this means “peak complexity” — to borrow a phrase from Mercedes’s management. Eventually, however, many of these factory workers will become unnecessary because electric motors are much simpler to build than diesel and gasoline engines. Last week's job cuts won’t be the last.

The German industry has been caught out too by an unexpected slowdown in demand. Continental AG, the supplier that’s cutting 20,000 jobs, expects production to stagnate over the next five years. Daimler said last month that sales haven’t matched its production capacity. Audi’s domestic plants are reportedly particularly under-utilized, not helped by the popularity of SUVs over sedans (the former tend to be built overseas).

Volkswagen, BMW and Daimler will still generate about 24 billion euros of net profit this year, according to analysts polled by Bloomberg. But the era of 10% operating profit margins — long a benchmark for German luxury carmakers — is over. Mercedes thinks 4% is more realistic next year.

The automakers therefore have to tackle their bloated fixed costs. In view of its spending commitments, Volkswagen was unwise to let its workforce swell to almost 700,000. That’s about 80% more than Japan’s Toyota Motor Corp., which builds a similar number of cars (though Volkswagen has a big truck unit too).

Volkswagen’s labor expenses have crept higher as a percentage of sales since the last recession. Doubtless this reflects the influence of the German unions and hence it’ll be very difficult to rectify. Like their peers, German employees at the Volkswagen brand have job guarantees until 2029.

Labor Bloat

VW's personnel costs have climbed as a proportion of sales

Source: Bloomberg

Ultimately the German car jobs boom was a bet that demand would increase, combustion engines would have a long life and global trade would remain encumbered. Instead, the electric shift is happening faster than expected and Trump’s tariff crusades have turned the German industry’s global production presence into a liability.

Cars are superfluous for many young people today, and if they do buy one it will soon have a simple electric motor, not a combustion engine made of hundreds of intricate components. The hiring practices of German carmakers look like a bubble that’s burst.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net