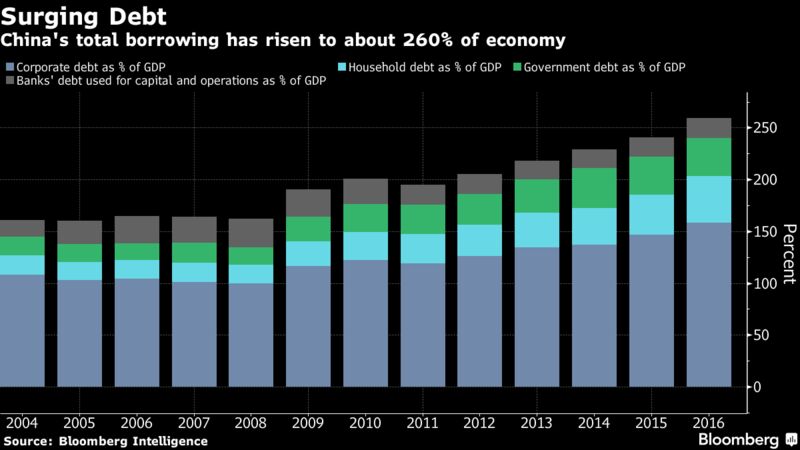

- CHINESE JUNK BONDS AND BANKING AMOUNTS TO OVER US$43-TRILLION AND BACKED BY A MERE US$2-TRILLION IN US BONDS WHICH IS ALSO CRUMBLING UNDER A PONZI SCHEME OF MONETARY FRAUD.

- WORLD DEBT TOTALS OVER US$217-TRILLION, THE LARGEST BUBBLE IN HISTORY AND ITS COLLAPSE IS BEING CONSTANTLY ADJOURNED BY QUANTITATIVE EASING AND BUY BACKS.

- ALL MARKETS (STOCKS, BULLION, BONDS (INTEREST) CURRENCY, COMMODITIES) ARE BEING MANIPULATED IN THE US, JAPAN, CHINA AND EU.

- INDIA IS THE LEAST CORRUPT.

S&P Global Ratings cut China’s sovereign credit rating for the first time since 1999, citing the risks from

The sovereign rating was cut by one step, to A+ from AA-, the company said in a statement late Thursday. The analysts also lowered their rating on three foreign banks that primarily operate in China, saying HSBC China, Hang Seng China and DBS Bank China Ltd. would

“China’s prolonged period of strong credit growth has increased its economic and financial risks,” S&P said. “Although this credit growth had contributed to strong real gross domestic product growth and higher asset prices, we believe it has also diminished financial stability to some extent.”

The downgrade, the second by a major ratings company this year, represents ebbing international confidence China can strike a balance between maintaining economic growth and cleaning up its financial sector. The move may also be uncomfortable for Communist Party officials, who are just weeks away from their twice-a-decade leadership reshuffle.

"It’s bad optics for China, especially when they’re out there from a policy and rhetorical standpoint talking

China’s Finance Ministry said in a statement Friday that S&P ignores the country’s sound economic fundamentals and that the government is fully capable of maintaining financial stability if it strengthens supervision and controls

The official Xinhua News Agency said in an analysis late Thursday that the downgrade won’t hurt foreign investment and doesn’t reflect the nation’s economic situation, citing experts.

Scholars at

The world’s second-biggest economy is forecast to slow after a robust first half, when it started the year with the first back-to-back quarterly acceleration in seven years, then surprised economists by matching that 6.9 percent expansion again in the second quarter. Economists surveyed by Bloomberg this month project growth will remain above 6 percent through 2019.

The International Monetary Fund last month increased its estimate for China’s average annual growth rate through 2020, while warning that it would come at the cost of rising debt that increases medium-term risks to growth. This month, IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde said at an event in Beijing that leaders are making critical efforts to rein in risk.

"The impact for

Gradual Deleveraging

While regulators are making efforts, deleveraging earlier

History suggests little relationship

Foreign investors make up less than two percent of the onshore bond market -- something policy makers are trying to change. Debt issued offshore by Chinese borrowers has been in effect mainly domestic, with local buyers taking up about 65 percent of bond sales in the first half of the year, according to Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd.

"The cuts of Moody’s and S&P don’t really reflect the international investors’ view on China’s economy," said Wang Tao, chief China economist at UBS Group AG in Hong Kong, adding that risks have been reduced, corporate profits are rising, shadow financing has been reined in and capital outflows contained, she said. "This is pretty behind the curve."

No Surprise

In the event that China were to default on its external debt, S&P said that three foreign banks operating there would be "unlikely to withstand a stressed scenario."

Moody’s cut its rating on China to A1 from Aa3 in May, citing similar concerns over economy

“The market has already speculated S&P may cut soon after Moody’s downgraded,” said Tommy Xie, an economist at OCBC Bank in Singapore. “This isn’t so surprising.”

— With assistance by Yinan Zhao, Xiaoqing Pi, Kevin Hamlin, Miao Han, Emma O'Brien, and Enda Curran

India: Economy

Growth in FY2017 (ending 31 March 2018) is expected to be lower than forecast in the Asian Development Outlook 2017 as a new tax regime poses transitory challenges to firms and as investment by state governments and private investors remain muted. A pickup is envisaged in FY2018, aided by restructured

GDP Growth: 7.1

Economic forecasts for South Asian countries

| Country | 2017f | 2018f |

|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 2.5 | 3.0 |

| Bangladesh | 7.2 | 6.9 |

| Bhutan | 6.9 | 8.0 |

| India | 7.0 | 7.4 |

| Maldives | 4.2 | 4.4 |

| Nepal | 6.9 | 4.7 |

| Pakistan | 5.3 | 5.5 |

| Sri Lanka | 4.5 | 5.0 |

| Average | 6.7 | 7.0 |

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

IMF Stress Tests Find $280 Billion Black Hole In Chinese Banks' Capital

The IMF released a new analysis on the instability stability of the Chinese financial system. Speaking to the media in an online briefing, some of the insights from Ratna Sahay, deputy director of the IMF’s Monetary and Capital Markets Department, hardly advanced our knowledge much.

That’s why the authorities are finally racing to contain the worst excesses of China’s insane credit boom following October’s Party Congress, for example overhauling the $15 trillion shadow banking and asset management sector. As we noted on the latter, the new measures don’t take effect until the end of June 2019, no doubt reflecting the enormity of the problems uncovered by Chinese regulators.

Sahay pointed to three main risks: credit growth, the complex and opaque financial system and implicit guarantees which “encourage excessive risk-taking” (think WMPs).

However, the IMF does a better job in explaining why a massive financial crisis in China is all but inevitable – the conflicting needs of social stability versus financial stability. According to Reuters.

But the near-termprioritisation of social stability seems to depend on credit growth to sustainfinancing to firms even when they are non-viable, it said. “The apparent primary goals of preventing large falls in local jobs and reaching regional growth targets have conflicted with other policy objectives such as financial stability,” the report said. “Regulators should reinforce the primacy of financial stability over development objectives,” the fund said.

Too late.

Xi Jinping and his predecessors allowed the excesses to go too far before Xi had solidified his grip on power sufficiently to intervene. The IMF itself has been missing in action when it comes to assessing China’s financial stability, as the latest report was the first of its kind since 2011. In terms of a financial system which has been out-of-control, we can use growth in the wealth management products (WMPs) as a proxy.

The IMF conducted stress-tests on 33 Chinese banks in a so-called “severely adverse scenario” and the majority failed. The capital shortfall even under this scenario was a staggering $280 billion dollars, about 2.5% of GDP. We should highlight – and we suspect it’s significance won’t be lost on readers – that the IMF stated in a footnote that the PBoC did not provide access to all of the “supervision data” it needed to properly conduct the stress tests. Bloomberg discusses the results.

China’s banks should increase their capital buffers to protect against any sudden economic downturn following a credit boom, the International Monetary Fund said. In its first comprehensive assessment of China’s financial system since 2011, the IMF recommended “a gradual and targeted increase in bank capital.” In a worst-case scenario, IMF stress tests suggested the country’s lenders would face a capital shortfall equivalent to 2.5 percent of China’s gross domestic product -- about $280 billion in 2016 -- together with ballooning soured loans.

Overall, 27 of 33 banks stress-tested by the fund, covering about three quarters of China’s banking-system assets, were under-capitalized by at least one measure. A larger financialcushion would better reflect potentially underestimated risks stemming from the banks’ exposure to opaque investments, and absorb losses as implicit government guarantees are removed, the fund said.

We are struggling to believe the IMF’s finding that the “Big Four” state-owned banks have sufficient capital. As we explained in detail in “How Ghost Collateral And Yin-Yang Property Loans Will Collapse China’s Credit Bubble”, there is an epidemic of fraudulent loans in China, with all parties, including the legal profession and the courts, complicit. At the same time, Xi is cracking down on the systemic corruption within government, so it doesn’t take much to link the two in the case of the Big Four. Nevertheless, Bloomberg notes the IMF’s assertions.

China’s top four banks, led by the world’s largest lender by assets Industrial & Commercial Bank of China Ltd., have enough capital, the fund said. But it said the nation’s smaller lenders, including those focused on individual cities “appear vulnerable.”

“Stress test results reveal widespread under-capitalization of banks other than the Big Four banks under a severely adverse scenario,” the fund said in its report. “Increasing capital would enhance the resilience and credibility of the financial system, as well as reassure markets.” The fund didn’t name the specific banks that need more capital.

There are some moments of mild tragi-comedy in the IMF’s report, for example, when it notes that the official proportion of non-performing loans in the Chinese banking system – 1.5% at the end of June 2017 – may understate the reality. Even using the official figures, China’s “debt at risk” exceeds most other major EM economies.

Trending Articles

Stress-testing the 22 Chinese banks under the “severely adverse” scenario, the IMF calculate that the non-performing loan ration would rise from 1.5% to 9.1%, cutting tier 1 capital ratios by 4.2%. Under these circumstances, bank would have to slow the pace of lending to the Chinese economy and the fiscal impact could exceed the direct recapitalization needs of the banking system “by a wide margin”, a.k.a a major crisis.

The PBoC responded surprisingly quickly to the IMF report. Regarding the very low official figure for bad debts, it noted that it resulted from banks having written off the bad ones, although obviously doesn’t square with the incredibly low number of defaults which continues to be a feature in the banking system. Bloomberg reports the response to the stress tests as follows.

Responding to the report, the People’s Bank of China said the assessment was generallyfair but disputed the IMF’s interpretation of the stress test results. “Comments about the stress test in the report do not fully reflect the results of the tests," the central bank said in a statement on its website Thursday. "China’s financial system has shown relatively strong capability to cope with risks.”

As we’ve found to our own cost on many occasions, hubris is not a good think when it comes to financial markets.

To its credit, the IMF’s staffers did place a lot of focus on the risk from guaranteed returns and off-balance sheet exposure in China’s $4 trillion WMP sector . Without calling it a Ponzi scheme, they identify the possibility of a bank-run.

“Off-balance sheet WMPs also represent a significant risk to capital,” the report said. “They are not guaranteed, but banks almost always compensate retail investors for principal losses. In a stress scenario, the costs to the banks of supporting WMPs could be substantial and could, in case of a run, place the liquidity position of some banks under strain.”

As part of the stress-tests, the IMF discovered four banks that could suffer liquidity shortfalls within 30 days, while confirming that the liquidity position of the Big Four was “strong” (hmmm ). Besides increasing bank capital, holding more liquid assets and reforming WMPs, we were intrigued by another of the IMF’s recommendations. The IMF stated that the PBoC and other regulators needed a substantial increase in staffing. We find this hard to believe… and very worrying… but the IMF found .

… the staff count at the “PBoC and the regulatory agencies has not risen in 10 years, while the financial sector has doubled in size.

It’s even less surprising how fraudulent lending grew into an epidemic in the Chinese financial system. What the IMF report doesn’t say is that it’s gone way too far to ever be reined back in orderly fashion. We are reminded of some Bank for International Settlements (BIS) analysis discussed by Bloomberg a year ago. The BIS found that the single most reliable indicator of looming banking crises is when the aggregate of credit to households and businesses exceeds GDP by more than 10% (as it did prior to the US subprime crisis). Needless to say, China was well past the point of no return.

No comments:

Post a Comment